The agreement, moreover, provided the state with much-needed funds and technical expertise. By the second decade of the twentieth century, it appeared to Iranian statesmen, such as Vosuq al-Dowleh, that with the collapse of imperial Russia, Iran’s role as a buffer state had come to an end and that its sovereignty and territorial integrity could be guaranteed only through the backing of British Empire, the winner of the war and the new master of the Middle East. In an exchange of letters between Cox and Vosuq al-Dowleh, Britain reassured Iran of its support for war reparations in the Paris Peace Conference and favorable renegotiation of all Anglo-Persian treaties.

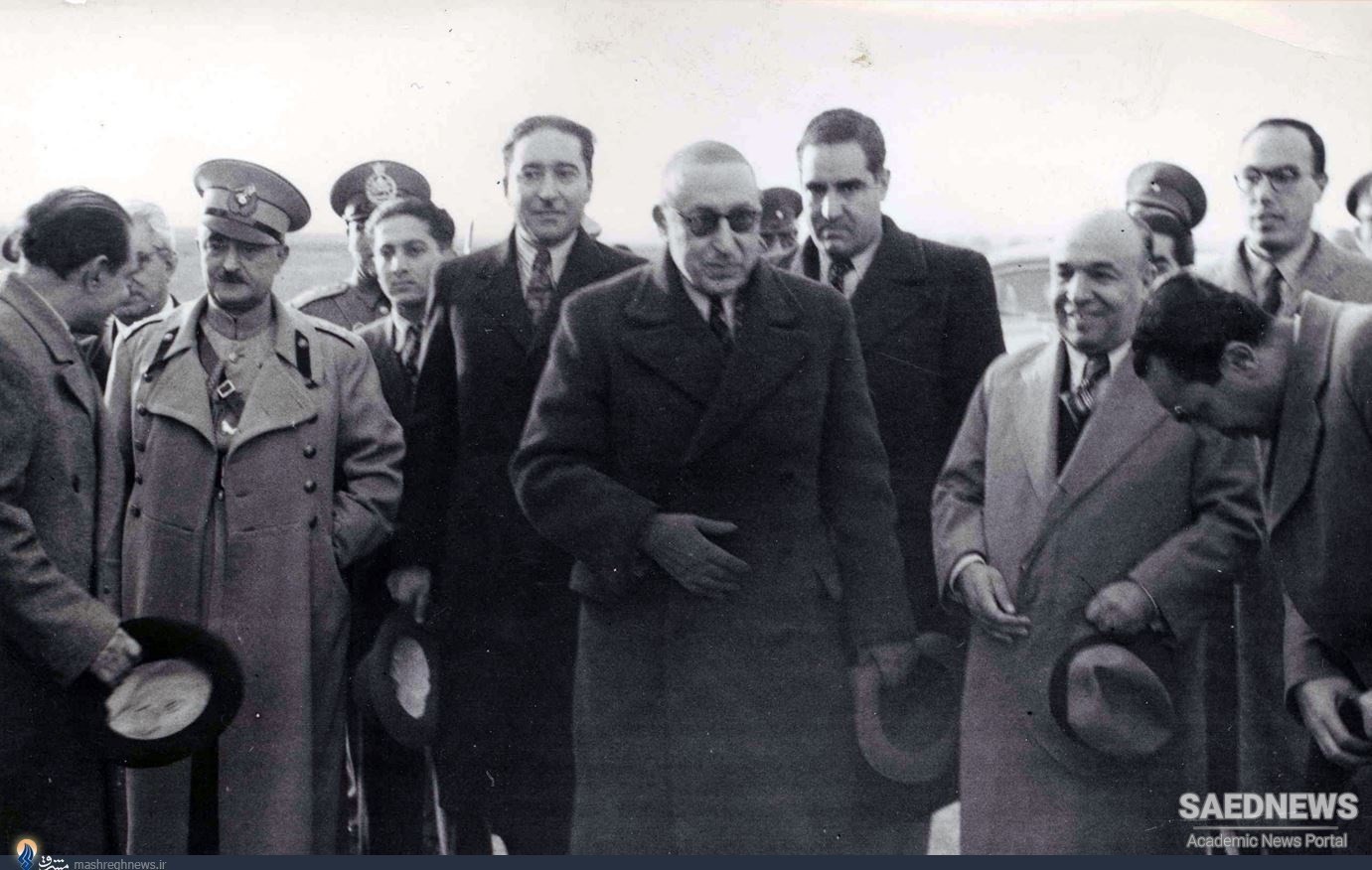

Yet behind the seemingly benign terms of the agreement, most Iranians detected the ghost of British hegemony. If any proof was needed, it was furnished, after the collapse of Vosuq al-Dowleh’s government in June 1920, in large monetary gifts paid by Cox to the premier and two of his chief ministers to lubricate the ratification of the agreement. The rumorridden political circles of Tehran opposed the agreement, and the nationalist press, with few exceptions, portrayed it as compromising Iran’s sovereignty. In this regard, the efforts of Vosuq al-Dowleh to present the agreement as the best Iran could afford under the circumstances did not succeed. A capable and cultured statesman of great erudition, who once served as the speaker of the first Majles, Vosuq hoped to leverage the agreement to bring political stability and economic reform.

Vosuq al-Dowleh, and his energetic foreign minister Firuz Mirza Nosrat al-Dowleh, were unfairly labeled in nationalist circles as traitors to the Iranian cause. Almost unanimous opposition to the agreement—which had yet to be ratified by the then suspended Majles—expressed by the burgeoning, though often naively sentimental, press. After a decade of national struggle, compliance with the spirit of the 1919 agreement discredited the Qajar nobility and its associated bureaucratic elite in the eyes of the urban intelligentsia.

The ANGLO-PERSIAN Agreement

The ANGLO-PERSIAN Agreement