The position of the Georgians in the Iranian army was as important as the position of the Armenians in the Iranian economy. In order to circumscribe the power of the Turkmens, the Safavid monarchs enrolled Georgian soldiers and appointed them to the highest military posts. In the Ottoman-Safavid wars of 1603-1604 the commander-in-chief of the Iranian troops was the Georgian Allahverdi Khan. As the Georgians were a foreign element, they did not have any local support and were entirely dependent on the monarch. Thus, the Shah was assured of their loyalty. Until the end of the Safavid period, the Georgians ‘formed the backbone of the Persian fighting forces’. Le Bruyn, who visited Iran in 1707, attests that the governor and the head of the army of Tabriz was a Georgian prince called Rustam Khan. The Carmelites testify that in 1711 the Iranian force sent to Qandahar for curtailing an Indian attack was composed mainly of Georgian soldiers.

There were also many Georgians and Circassians taken as slaves to the court. After the reign of Shah Tahmasp (1524-1576) the number of Georgian and Circassian women had increased to such an extent that all the Christian relics brought by the European missionaries to the court were sent to the seraglio. The mother of Shah Abbas I was a Caucasian Christian, and he himself had Christian wives, one of whom was the daughter of Simon Khan, a Georgian prince. Father John Thaddeus asserts that Shah Safi (1629-1642) had not been circumcised. His mother was Georgian, and he too had many Georgian wives. Shah Abbas II (1642-1666) had also married Caucasian women.His son, Shah Sulayman (1666-1694) was born of a Circassian slave.

The large presence of Christian women in the royal harem and of Christian slaves at court certainly had some repercussion on the political level. Indeed, many of these Caucasian women were of royal descent and wanted the court to comply with their wishes. It is difficult, however, to evaluate how beneficial this Christian presence was to the Armenians, for the doctrinal differences between the different creeds of the Armenians and Georgians had historically made the two groups hostile towards each other. The intervention of the Georgian princesses apparently served more the purpose of foreign Christian merchants or missionaries, who wished to obtain commercial concessions or intended to establish convents in Iran. Along with the Georgian princesses, Georgian princes were also taken to Isfahan. The Shah chose from among them the heir to the Georgian throne, and made the chosen prince the governor of Isfahan after having converted him to Islam. He was put on the throne of Georgia after the death of the ruling Georgian monarch.

It should be mentioned that not all the Georgians ended up in the army or the court. Savory says that in 1614 alone, there were 130,000 Georgian prisoners brought to Iran. They were scattered all over the country, and unlike the Armenians, who were able to preserve their religion, they were assimilated to the local population. The European missionaries had endeavoured to win a number of them back to Christianity, but their successes were temporary as the Georgian and Circassian communities were dispersed in such a way that it was difficult for them to maintain their ethnic cohesion.

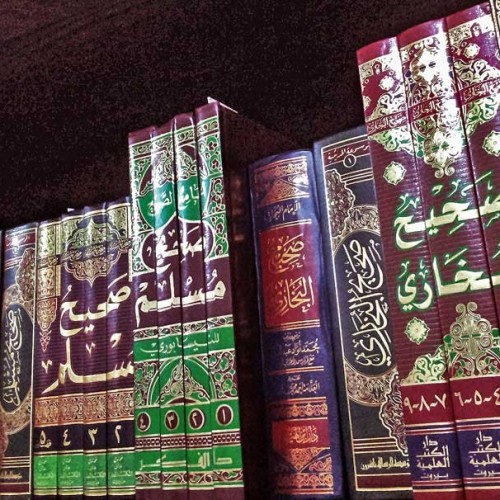

The Method of Shi’ism in Authenticating and Following the Hadith

The Method of Shi’ism in Authenticating and Following the Hadith