The immediate occasion of the rising which followed was Alexander's order to the local chiefs to assemble for a conference at Bactra, an instruction which was thought to mask some sinister purpose. The communities along the Jaxartes rose and put to death their Macedonian garrisons. Altogether seven walled towns shut their gates on Alexander. These were rapidly reduced by his energetic siege operations, the most considerable of the cities being Cyropolis, a settlement of which the name survives in the present-day Kurkath. The Macedonians in revenge put to death all the male inhabitants of these towns, and enslaved the women and children.

Meanwhile Alexander's forces were being threatened on two other fronts. On the north bank of the Jaxartes a force of Saka horsemen had assembled, and were preparing to attack the Macedonians. At the same time news was received that the garrison which had been left behind at Maracanda was being besieged by the local chief Spitamenes. With covering fire from his siege-catapults, Alexander was able to send his forces across the Jaxartes and disperse the Sakas. But reinforcements sent to relieve the garrison at Maracanda were caught at a disadvantage during an incautious pursuit of the enemy, and were defeated with heavy losses. It was only when Alexander brought up his main army by forced marches from the Jaxartes that the situation was restored.

Soon afterwards, Alexander went into winter quarters at Bactra. But towards mid-winter he moved out with five columns and crossed the Oxus to suppress unrest in Sogdiana. Spitamenes consequently transferred his activities to the south bank of the river, and even attempted a raid against Bactra itself. However, he was ultimately defeated in a number of engagements with detachments of the Macedonian cavalry, and eventually returned to Sogdiana. There his Saka auxiliaries turned against him, cutting off his head and sending it to Alexander. Or, if the version of Quintus Curtius (vm. iii. 13) can be believed, the murder of Spitamenes was the act of his estranged wife.

The turning point in Macedonian relations with the people of Sogdiana was Alexander's marriage to the Iranian heiress Roxana, daughter of the influential chief Oxyartes, a prominent leader of the local resistance to the conqueror. When a mountain stronghold of Oxyartes was captured by the Macedonians, Roxana fell into Alexander's hands. Subsequently he was able to win over Oxyartes, who in turn effected Alexander's reconciliation with Chorienes, another chief who was still resisting. Thus the bitter hostility which the people of Bactria and Sogdiana had initially displayed towards the Macedonians was replaced by a mutual understanding, and Alexander was able to enlist the Sogdian, Bactrian and Saka cavalry who served him well in India at the battle of the Hydaspes.

There is also evidence that Alexander settled in the garrison cities of eastern Iran large numbers of homeless Greek mercenary soldiers. Some of these were no doubt Greek mercenaries who had been in the service of Darius III, though the majority were detachments from Alexander's own forces. The settlements provided the nucleus for the substantial Greek colonization of Bactria and Sogdiana which was to become an important factor in the history of the 3rd and 2nd centuries B.C. Yet these involuntary settlers did not always perform with docility the role for which they had been chosen. In 326 B.C. when Alexander was recovering from wounds sustained during fighting against the Malli in India, a rumour of his death reached the settlers in Bactria and Sogdiana. Weary of their long exile in a distant land, about three thousand men banded themselves together to march back to Greece, but the sources are in conflict as to their fate. Diodorus (xvn. 99. 5) reports that they were massacred by Macedonian troops, but according to Quintus Curtius (ix. 7) they reached their homes. A more serious mutiny of the settlers took place after Alexander's death at Babylon in 323 B.C. According to Diodorus (XVIII. 7. 2) no less than twenty-three thousand men mutinied and set out on their homeward march. They were intercepted and massacred by Macedonian forces sent out from Babylon by Perdiccas under the command of Pithon. Tarn, however, believed that this figure for the number of mutineers was greatly exaggerated.

After Alexander's death the satrapies of his empire were divided between his officers. Sibyrtius received Arachosia, and Oxyartes, the father of Roxana, was confirmed as satrap of the Paropamisadae along the Kabul river. To Stasanor was allotted Aria and Drangiana, whilst Philip retained the satrapy of Bactria and Sogdiana. During the War of the Successors all these governors supported Eumenes against Antigonus; but after his final victory near Isfahan Antigonus returned to the west, leaving them undisturbed in possession of their satrapies.

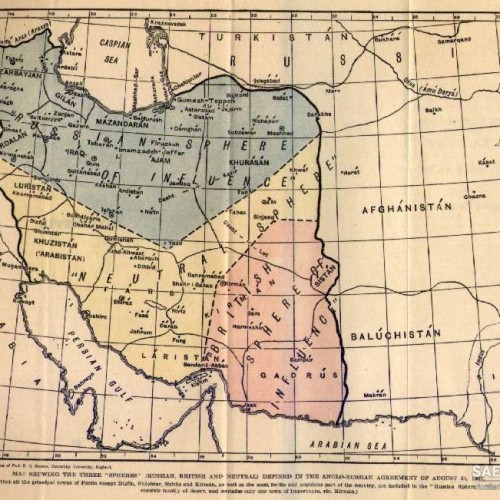

The Havoc Brought upon Iran by Anglo-Russian Friendship

The Havoc Brought upon Iran by Anglo-Russian Friendship