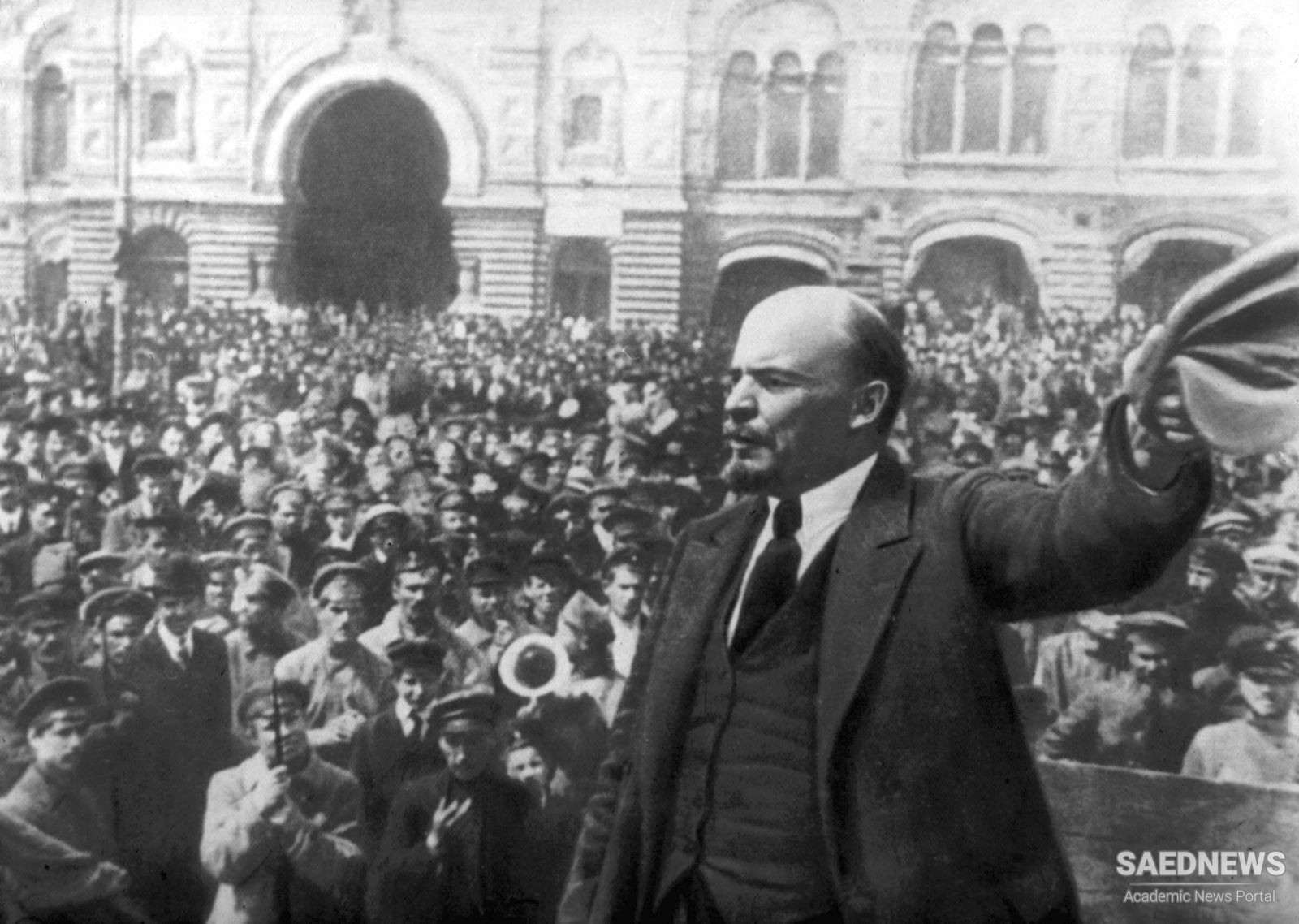

The eventual defeat of the Ottomans on the Mesopotamian front and the British capture of Baghdad in January 1917 shattered the nationalists’ hopes for recovery on the western Iranian front. To many it appeared as if their country would never recover from the bouts of political chaos and foreign intervention. Yet the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917 rekindled Iranian aspirations at a time when Germany and its Turkish ally were rapidly losing their strategic gains—and with it their credibility. With the exception of the Great War itself, perhaps no other international event left as lasting an effect on Iran’s early twentieth-century history. The collapse of tsarist Russia, then in control of nearly two-thirds of Iranian territory, both terrified and exhilarated Iran. Fear of the Bolshevik regime and its communist ideology heightened among the elite as the Red Army moved closer to the Caucasus and the Iranian border. On the one hand, as became apparent in early 1918, the collapse of imperial Russia promised an end not only to Russian occupation but also to more than a century of its hegemonic ambition. That Iran could escape what had appeared to be almost certain disintegration— the north annexed by Russia and the south by Britain—could hardly be considered anything less than a miracle.

As early as December 1917, the vulnerable Bolshevik regime, searching for regional allies, denounced the 1907 Anglo-Russian Agreement as a ploy of Western imperialism and called on the world to allow Iran to decide its own destiny. By June 1919 Moscow not only rescinded all of Iran’s loan commitments due to Russia but also repealed all the public and private concessions acquired by the tsarist regime as early as the capitulatory privileges of the 1828 Treaty of Torkamanchy. Moreover, it handed over to Iran most of the Russian port facilities on the Persian side of the Caspian and the sector of the Julfa railroad on Iranian soil, and it gave Iran control of the Russian Mortgage Bank. Nullification of these concessions was finalized in the 1921 Soviet-Iranian Treaty of Friendship, which was skillfully negotiated by Iranian diplomats in the face of British obstruction.

Despite these friendly gestures, the appeal of communist ideology to many Iranian nationalists was by no means imminent. Many Democrats who entertained a homegrown socialist ideology admired the Bolshevik revolution and the new Soviet model, but not slavishly. Democrats in Shiraz, for instance, well equipped and in good morale, welcomed the Russian Revolution as a lifesaving breakthrough that could unravel the SPR’s hold over the south (fig. 7.5). The conservative statesmen in Tehran were mostly accustomed to the Anglo-Russian rivalry or, worse, subservient to Britain and its hostility to the Bolsheviks. Nevertheless, by 1918 the premier Samsam al-Saltaneh took advantage of the new regime’s friendly gestures and, much to the anger of the British, unilaterally denounced the 1907 agreement and canceled all privileges for any foreign powers in Iran.

The instability of successive short-lived governments in Tehran, however, did not allow for more serious engagement with the Bolsheviks. Yet, despite the cool reception at the capital, soon the majority of the Iranian polity began to feel the Soviet ideological and military presence. As early as the end of 1919, Bolshevik partisans landed in the Caspian port of Anzali, with the apparent intent to recapture the Russian fleet and dislodge the loyalist detachments of the Russian counterrevolutionary White Army from northern Iran. They advanced as far south as the vicinity of Qazvin before being pushed back by Iranian regular forces and units of the Cossack brigade.

The Battle of Isfahan

The Battle of Isfahan