The seat of the Nestorian patriarchate at Baghdad, which had survived all the peripeteia of history since the Sassanian period, had not been able to overcome Timur Lang’s onslaught in 1392. Timur Lang’s assault caused the dramatic decline of the Nestorian population and the removal of the Nestorian seat from Baghdad. The Nestorian Patriarchate then became a hereditary office until 1551, when the cohesion of the community was destroyed.

There were certainly many factors which had created this division, but the two most important ones were the meddling of the Catholic missionaries and the division of the territories inhabited by the Nestorians between the Ottomans and the Safavids. The missionaries say that the Patriarchs residing in Azerbaijan claimed authority over the Nestorians living in Ottoman territory. However, their power had dramatically waned since the 13th century, and there was not much left of the glorious days when they had spiritual jurisdiction over most of the Christian churches in Asia. By 1606, there were hardly any contacts between them and the Nestorians in India.

The only Nestorians left in Iran were gathered around the town of Urumia. According to the Carmelites, in the 17th century there were about 5,000 Nestorian families living there, and a few families scattered in Maragha and near the town of Solduz. A number of them were deported to Isfahan along with other non-Muslim groups by Shah Abbas I at the beginning of the 17th century. Tavernier and Pietro della Valle confirm their presence and say that there were also some Jacobites in the town.

In Isfahan, their fate was very similar to that of Armenians. Certainly, the part they played in the Iranian economy was much more modest; however, the Nestorians were also very active at the commercial level and had built themselves a reputation for their craftsmanship.802 Shah Abbas’ interest in them confirms their abilities in those occupations. Like the Armenians, they also suffered from the edict of Shah Abbas I which made any of their Muslim relatives the sole proprietor of their possessions. In 1621, which appears to be the year the edict was proclaimed, about thirty Nestorian families converted to Islam and seven left Isfahan.

The Catholic missionaries strove to convert those of them who had remained Nestorians. They were quite successful, as the Nestorian religious establishment was not as powerful or influential as that of the Armenians, and therefore there was less resistance towards the activities of the Catholics. Nonetheless, the Armenians not only wished to protect their own community from the Catholic missionaries, but also desired the Catholic population not to increase. In 1650, they obtained an edict prohibiting Catholic missionaries from officiating to Nestorians. This proves further that the presence of the Catholic missionaries was not politically beneficial to the Armenians, and that the Armenians considered themselves the leaders of all the Christians in Iran.

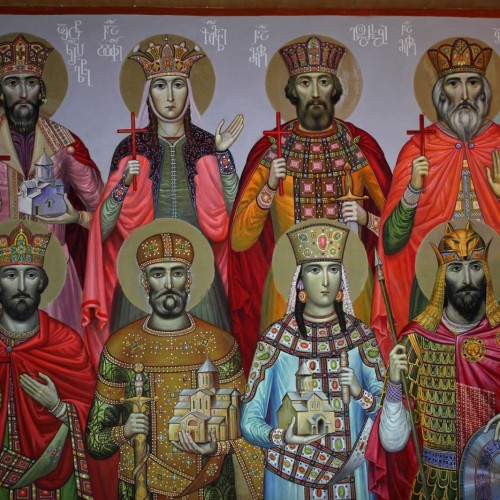

The Georgians and Circassians: The Assimilated Christians

The Georgians and Circassians: The Assimilated Christians