By the middle of the nineteenth century four dimensions of royal authority underscored Iran's historical experiences. The first was the pre-Islamic tradition of kingship as transmitted through political culture and practice of government and through manuals of government, general histories, and epic legends such as Firdawsi's Shahnama . The second was the Islamic, and more specifically the Shi'ite, dimension of government, which essentially aimed at reconciling Persian kingship with the complex notion of political authority in Islam. The third was the nomadic concept of power and leadership, which at least since the Turkish and Mongol invasions of the eleventh to fourteenth centuries had been a persistent feature of the Islamic state. The final influence was the modern Western model of government and examples of European kingship as they became known to Persian (and other Middle Eastern) rulers from the early decades of the nineteenth century.

The Persian monarchical model, a legacy of the Sassanian period 244–640) and before, persisted for centuries in the Islamic world with few interruptions. After the decline of the Abbasid caliphate in the ninth century, for all intents and purposes the institution of the sultanate was a revival of the Persian model. But even before that the Buyid rulers of central and southern Iran (932–1062), who were of Shi'ite persuasion, had adopted the Persian imperial title of "king of kings" (shahanshah ), whereas their Sunni rivals, the Samanids of Khurasan and Central Asia (819–1005), proud of their Sassanian lineage, had upheld the old courtly practices and patronized the revival of Persian language and culture. In the heyday of the Ghaznavid (998–1050) and the Saljuqid (1038–1194) empires, when loyalty to the caliphate was strong and when the Turkish ancestry of the sultans was pronounced, and later during the Ilkhanid period (1256–1335), Persian ministers were successful in persuading the rulers to embrace a traditional kingly posture and to observe the norms of monarchical rule. The celebrated Persian minister Khwaja Abu-'Ali Hasan Nizam al-Mulk (d. 1092), who considered the symbiosis between monarchy and "good religion" as a basis for social stability, was indeed advocating a theory set forth by Zoroastrian writers of the sixth century.

This aspect of kingship, the need for compatibility between state and religion, was further stressed in the Safavid period, with the Shi'ite shahs claiming a dual authority. They were viewed both as temporal rulers presiding over the state and, at least up to the early seventeenth century, as deputies of the Shi'ite Imam and thus as custodians of the Shi'ite community. Safavid rulers enhanced such a merging of temporal and religious spheres by granting patronage to Twelver Shi'ite 'ulama and incorporating them into the state apparatus. However, the Safavid shahs did not abandon their royal premises and practices. The subjects of the Safavid empire regarded the monarchy, if not the person of the shah, as an exalted institution crucial for preserving Shi'ism within its oft-threatened boundaries. That there were attempts to resuscitate the Safavid monarchy— including several by pretenders claiming Safavid descent—attests to the endurance of this temporal-religious model for at least half a century after that dynasty's demise. The early Qajars did not claim to be of Safavid descent, nor did they pretend to rule on behalf of a nominal Safavid shah—as did Nadir in his early days and Karim Khan, the vakil (deputy), throughout his rule—but they nevertheless tired to sustain an air of legitimacy as protectors of the Shi'ite domain and upholders of the Shi'ite religious order.

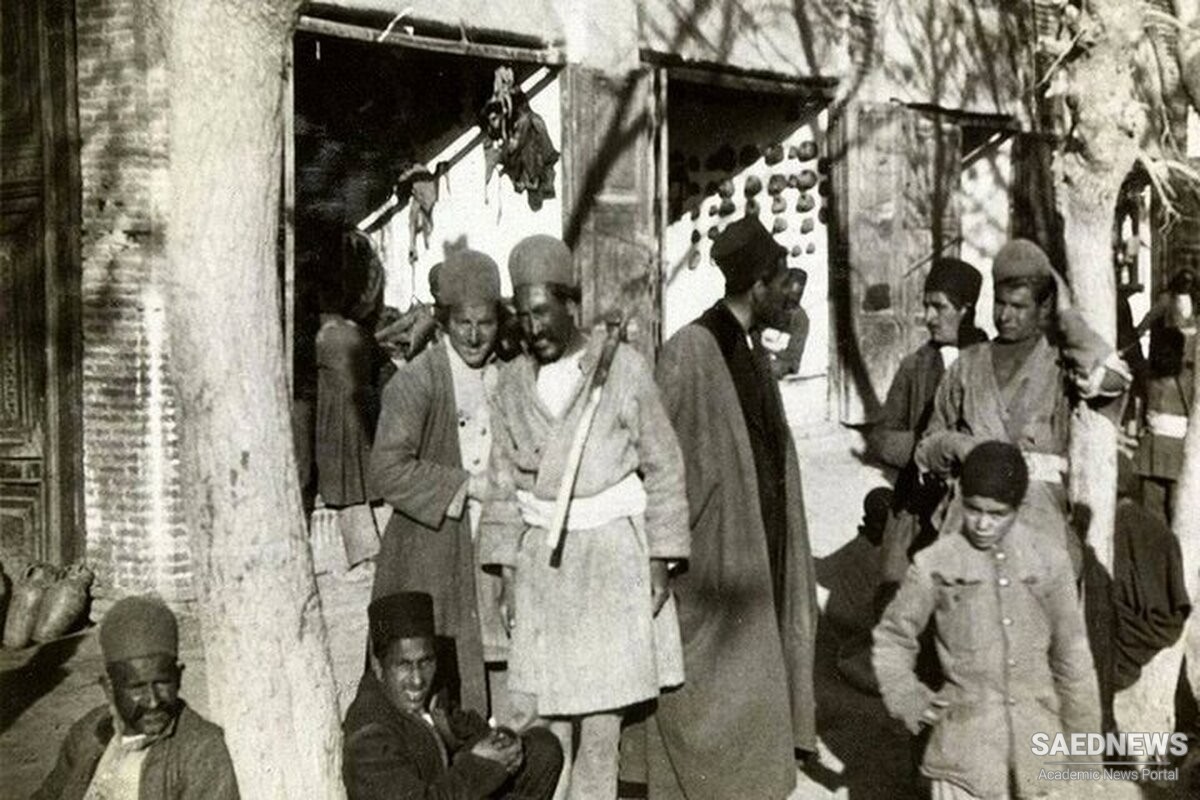

Equally important for the Qajar dynasty's survival, however, was its ability to maintain a notion of social justice in its dealings with its subjects. Around the patrimonial figure of the shah were shaped the institutions of government, and through him the bonds with his subjects were forged. The early Qajar rulers honored, at least in principle, the paradigm that divided the state (dawlat ) from the subjects (ra'iyat ) and defined the place and functions of each of the two components. The shah viewed his bond with the subjects—the peasants, the urbanites, and the nomads—as one of a social contract; in exchange for the state's providing security and order, the subjects were expected to remain obedient and economically productive. In such a model the shah was at the top of the social pyramid and the ultimate exemplar within a hierarchy that replicated his patriarchal authority at all lower urban, tribal, and familial levels. Every man of stature and authority—the 'ulama, landlords, chiefs of tribes, city wardens, chiefs of the merchants, masters of the guilds, and leaders of the sufi orders—was expected to mind his flock and be responsible for its conduct.

Notwithstanding the patrimonial nature of royal authority, the PersoIslamic model of state summed up the duties of the ruler in two complementary functions: defense of the kingdom from external threats and administration of justice within the kingdom. In reality, defense of the land required nothing more than mustering the military forces necessary to quell any invasion or organized rebellion (often of a nomadic nature), whereas dispensing justice was synonymous with preserving the societal order against forces of religious sedition and popular chaos. Discharging these duties required a basic division between the ruler and the ruled, which in turn necessitated intermediary agencies to enforce the royal authority. The rationale for the tripartite interplay between the ruler, the government agents, and the subjects was therefore explained in the form of a causal cycle, the so-called "cycle of equity," the maintenance of which was the ruler's responsibility. The kingdom's survival and that of the king as its head, it was argued, required maintaining an army and a bureaucracy in order to defend the land, enforcing the ruler's command, and collecting taxes. But the revenue could only be generated by the subjects if they lived in peace and security. It was thus incumbent upon the king to ensure that the subjects were treated justly and were immune from his agents' natural tendencies toward oppression. If he failed to do so, the kings were warned in no unsure terms by the authors of government manuals, he would foster popular sedition and rebellion, which would soon remove him from the throne and destroy his dynasty.

This rudimentary formula engendered a certain tension within the institution of kingship. It required the ruler to supervise the government apparatus and yet keep a distance from it in order to protect the subjects against the excesses of his own agents. This was often resolved by the ruler's being partially excluded from the routine of governing. Practical power was delegated to ministers and high-ranking officials, but the ruler reserved for himself the discretionary rights of dismissing and promoting, punishing and rewarding. These rights were bestowed upon him because he was considered the locus of divine glory and possessor of royal charisma (farr-i shahi ). He was the "shadow of God [zillullah ] on earth," but if he was not capable of maintaining the delicate balance between the government and the subjects he was destined to lose his divine mandate and with it his glory and his throne.

In principle the Qajar shahs, like their predecessors, were aware of these royal duties and recognized the conditionality of their divine mandate. Yet contingencies of their office inevitably occasioned a certain political isolation against which it was hard to prevail. This was intensified by elaborate court protocol, by bureaucratic practices that limited public access to the shahs, and by their desire for material gains, their fears and insecurities, and their own private lifestyles. Even though they made occasional attempts to break through the strictures of their office by reducing the power of their officials or eliminating administrative and courtly barriers by personally hearing the grievances of their subjects, they could hardly escape the mores of the monarchy itself. The spectacle of kingly glory on which the ruler's authority rested required from him lofty gestures of generosity and tempered severity but seriously limited his ultimate task of preserving the balance between the ruling elite and the ruled.

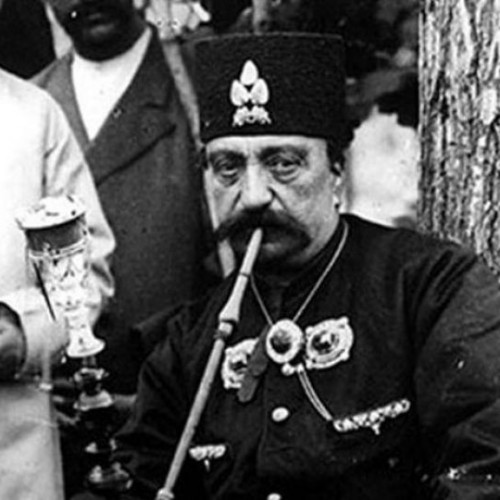

The self-image of the Qajar shah as the nucleus of the ruling elite and as the supreme regulator with divine rights is evident in the use of titles and honorifics and the way these evolved over time. Although the chronicles of the Qajar period showered Aqa Muhammad Khan with many grand appellations, during his own time as ruler he adopted no more grand a title than khan and later shah . By contrast, his successor, Fath 'Ali Shah, adopted not only the ancient Persian title of shahanshah ("king of kings") but also the Torco-Mongol title of khaqan ("the khan of the khans"), symbolizing claims over both the throne and the tribes. This lineage was underscored among Fath 'Ali Shah's successors: Muhammad Shah was referred to as "Khaqan son of Khaqan," Nasir al-Din Shah as "Khaqan son of Khaqan son of Khaqan."

These royal titles were embellished with an array of other honorifics reflecting the rulers' desire to present a sense of historical continuity and hence legitimacy. Drawing on the glories of the Persian mythical and dynastic past, the Qajar shah was acclaimed by court chroniclers and in official records as a "world conqueror" (gity sitan ) of "Alexandrian magnitude" (sikandar sha'n ), a possessor of Jamshid's glory (Jam jah ), of Faridun's charisma (Faridun farr ), and of Khusraw's splendor (Kisra shawkat ). During times of war and punishment he was a Turk with the ferocity of Genghis (Changiz sawlat ) and the vehemence of Tamerlane (Timur satwat ). In peacetime he was acknowledged as a "joyous king" (shahryar-i kamkar ) and a fortuitous sultan (sultan-i sahab-qaran ) whose religious and civil duties were also couched in his titles. Above all he was the "shadow of God" (zillullah ) upon earth, a "refuge of Islam" (Islam panah ) and a "shield of the Islamic shari'a" (shari'at panah ), but he was also a "guardian of the Persian kingdom" (hafiz-i mulk-i 'ajam ) and more frequently the king (padshah ) of the "Guarded Domains" (mamalik-i mahrusa ) of Iran.

Ample use of grand titles was a practice not limited to the ruler. All the princes of the royal family, members of the nobility, courtiers, government officials, and army officers—and later, under Nasir al-Din, the shah's chief wives, all the servants of the inner court, and even those casually connected to the sprawling Qajar court—held titles often unsuitable to their stature and function. For the early Qajar rulers, conferring titles was a way of enhancing the image of royal magnificence. For the recipients it was a means of acquiring legitimacy in place of rendering service and loyalty. In the highly ceremonious court of Fath 'Ali Shah there was some rationale for granting titles, but by the late Nasir al-Din period and that of his successor, Muzaffar al-Din Shah (1896–1906), there was little meaning in such titles beyond the size of the gift presented to the shah or the ruler's personal favor toward the recipient.

Qajars: From Tent to the Throne

Qajars: From Tent to the Throne