Bahrain's forces were defeated in Mesopotamia, and by a flanking movement one of Khusrau's lieutenants seized Ctesiphon. Bahram was a brilliant general, however, and even with inferior numbers he was able to inflict large casualties on his enemies. None the less he was obliged to retreat to Azerbaijan and in a decisive battle Khusrau, with his Byzantine and Armenian allies, was able to defeat Bahram completely. Bahram fled to the Turks, where he remained for a year until he was assassinated, probably at the instigation of Khusrau.

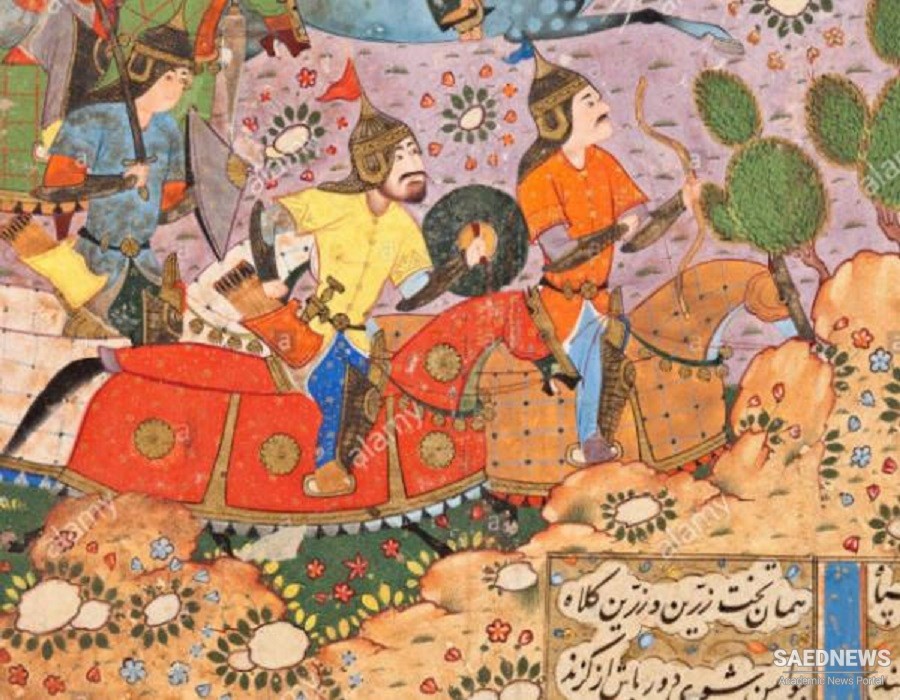

The life of Bahram Chobin was told in a Pahlavi romance which passed into Persian and Arabic versions. Firdausl gives the essentials of the story of the rise and fall of Bahram in his Shdh-ndma, and the hero is revealed as the heroic prototype of a Persian chevalier or knight. His exploits, greatly embroidered of course, remained in the memories of Persians for centuries. Although he was in the end unsuccessful, his human qualities gave him a greater place in the hearts of his countrymen than the king of kings, as witnessed by the stories.

Khusrau II rewarded those who had supported him and executed his opponents. One of the former, who received many honours and a governorship, was the Armenian Smbat, head of the house of Bagratuni. With regard to his uncles who had supported him, Khusrau was in a dilemma, since they had overthrown his father. He finally seized Bindoe and drowned him, whereas Bistam escaped and raised the standard of revolt in the Alburz mountains. On the plateau Bistam was able to maintain himself for almost a decade, for the battles with troops sent against him by Khusrau were indecisive. Bistam was able to prolong his resistance in great part because of the support given him by former partisans of Bahram Chobln. So in effect Bistam was a successor of Bahram. He established his capital at Ray and minted coins, thus showing his claim to rule instead of Khusrau. Finally Bistam was murdered by one of his eastern allies, a Hephthalite or Turkish chief. By 601 Iran was once more united under Khusrau, but it had been weakened greatly by the internal strife.

The territory promised by Khusrau to Maurice was ceded to Byzantium by a treaty in the autumn of 591, and peace reigned between the two empires. The Ghassanid Arabs, clients of the Byzantines in Syria, however, raided Persian territory which caused Maurice to send as his envoy George, the praetorian prefect or commander of the eastern forces of Byzantium, to Khusrau to assure him that the Arabs had acted on their own. Peace was reaffirmed and declarations of continued friendship were so strong that some Armenian writers believed that Khusrau had been converted to Christianity. He had a Christian wife called Shirin, and legend also assigned to him as another wife Maria the daughter of Maurice, which was most unlikely. Here again the legend of Khusrau and Shirin in Persian poetry had many ramifications. Although the king was himself not a Christian, he did show considerable sympathy to Christians, and he even gave money or presents to Christian shrines. In the writings of Christian authors Khusrau II has received a good name.

Until the overthrow of the emperor Maurice by Phocas in Constantinople, we hear little about Byzantine-Persian relations in this reign, or about the internal affairs of the Sasanian empire. We may presume that Khusrau was occupied with the revolt of his uncle and in consolidating his position. He obviously had to reward the Byzantine soldiers who had helped him to the throne, and some Persians felt he was too friendly to their traditional enemies. Likewise the supporters of Bahram Chobln were not all executed or even removed from office, and many Persians opposed to Khusrau still held positions of authority. Among those who incurred the enmity of the king of kings was Nu'man III, the Nestorian king of the Lakhmid Arabs with their capital at Hira. Some sources say that the Arab king had not helped Khusrau when the latter had fled to Byzantine territory and requested Nu'man to come with him, but this is unlikely. There were many reasons, however, for the enmity of the two monarchs, and it seems in the early years of Khusrau's reign hostilities broke out between the Arabs and Persians. Nu'man was captured by a ruse about 602 and later he died in prison.

Khusrau resolved to end the dynasty of the Lakhmids, so in their place a chief of the Tayy tribe was made head of the Arabs under Persian control, but with a Persian governor at his side. The new situation disturbed the status quo and bedouin Arab tribes felt free to raid the settled areas of Iraq. A large tribe, the Bakr, allied with other Arabs, met the Persians and their Arab allies in the famous battle of Dhu Qar. The Persians were decisively defeated, which showed the Arabs their strength when united. It also revealed the weakness of the Sasanian defence system on the edge of the desert once the Lakhmids were gone. The old system had not only held the Arabs at bay, but the Lakhmids had also maintained a far-flung hegemony over warring tribes which could have caused much trouble for the Sasanians. The way for the expansion of Islam was indicated by this battle which took place about 604, although the exact year is unknown.

Egypt: the Rise of a New Civilization

Egypt: the Rise of a New Civilization