In urban Iran, physical exercises were carried out by male athletes, termed pahlavans, in zurkhanehs, houses of strength (or force), which date back at least to Timurid times. The main function of the various exercises was to prepare athletes for wrestling, then the only zurkhaneh discipline that was competitive. The best wrestlers found employment at Court and at the establishments of elite Iranians whom they entertained with their displays of strength and dexterity. Since there were no weight classes, the most successful athletes were also the heaviest, and pahlavan connoted someone who was, if not obese, at least bulky.

In 1874 Prince E‘tezad al-Saltaneh,9 the minister of science of Naser al-Din Shah (r. 1848–96), asked the Dar al-Fonun school in Tehran to draw up a manual of gymnastics and wrestling based on the traditional exercises of the zurkhaneh. Iran was in the midst of a famine and two epidemics,10 and the shah hoped to improve public health by encouraging physical exercise. The Dar al-Fonun, founded in 1851 and Iran’s only modern school at the time, employed a number of European teachers and was an appropriate setting for such an endeavour. The general Qajar attitude to European culture was to adapt rather than to adopt;11 taking native practices and systematizing them for a novel purpose was in line with such an outlook. The resulting treatise, authored by one ‘Ali Akbar b. Mehdi al-Kashani, bears the title Ganjineh-ye koshti (Treasure of wrestling), but it was not published and zurkhaneh exercises were never introduced in Iranian schools.

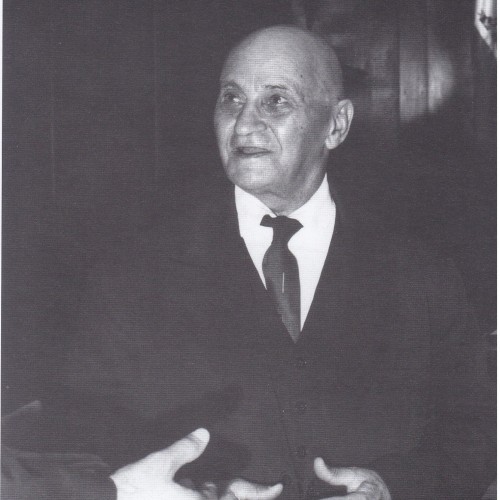

One can only guess why the project was never implemented. One reason may be the generally haphazard, unsystematic, and short-term manner in which reforms were instituted in the Naseri era. But there is probably more to the disinclination to introduce the ways of the zurkhaneh to the nascent modern educational system. Contrary to the official narrative on “ancient sport” that came into being in the 1930s, which presented the institution as a depository of noble and chivalrous values inherited from Persia’s glorious preIslamic past, zurkhanehs had a much more ambiguous reputation in Iranian society. While many were indeed imbued with spirituality, others attracted thuggish elements that at times terrorized neighbourhoods. Hygiene was poor, and it was well known that homoerotic practices were tolerated in some of them.14 In other words, they were not the type of institution from which patriotic reformers, bent on revitalizing the Iranian nation, could draw inspiration. It is therefore not astonishing that the pioneers of modern sport in Iran almost completely ignored the zurkhaneh tradition and preferred to import Western methods wholesale; in Varzandeh’s writings we do not find any reference to Iran’s traditional exercises.

And yet, it was the tough, bulky pahlavans of the zurkhaneh and their heavy muscle-building instruments that informed the average Iranian’s conception of athleticism and manliness. The Swedish callisthenics taught by Varzandeh struck traditional people as frivolous if not effeminate, and he was criticized for making his pupils dance, dancing being considered a dishonourable activity. ‘Isa Sadiq, a pioneer of modern education in Iran, wrote in his memoirs that Varzandeh’s efforts were met with hostility by conservatives, who called callisthenics varjeh-vurjeh (horsing around) and declared them to be contrary to human dignity: “But with his pleasant demeanour, wit, and sacrifice Varzandeh was able to set up physical education classes in a few schools.”

Mir Mehdi Varzandeh

Mir Mehdi Varzandeh