We can trace the chain of human descent back to the appearance of vertebrates, or even to the photosynthetic cells and other basic structures which lie at the start of life itself. We can go back further still, to almost unimaginable upheavals which formed this planet and even to the origins of the universe. Yet this is not ‘history’. Common sense helps here: history is the story of mankind, of what it has done, suffered or enjoyed. We all know that dogs and cats do not have histories, while human beings do. Even when historians write about a natural process beyond human control, such as the ups and downs of climate, or the spread of a disease, they do so only because it helps us to understand why men and women have lived (and died) in some ways rather than others. This suggests that all we have to do is to identify the moment at which the fi rst human beings step out from the shadows of the remote past. It is not quite as simple as that, though. First, we have to know what we are looking for, but most attempts to defi ne humanity on the basis of observable characteristics prove in the end arbitrary and cramping, as long arguments about ‘ape-men’ and ‘missing links’ have shown. Physiological tests help us to classify data but do not identify what is or is not human. That is a matter of a defi nition about which disagreement is possible. Some people have suggested that human uniqueness lies in language, yet other primates possess vocal equipment similar to our own; when noises are made with it which are signals, at what point do they become speech? Another famous defi nition is that man is a tool-maker, but observation has cast doubt on our uniqueness in this respect, too, long after Dr Johnson scoffed at Boswell for quoting it to him. What is surely and identifi ably unique about the human species is not its possession of certain faculties or physical characteristics, but what it has done with them. That, of course, is its history. Humanity’s unique achievement is its remarkably intense level of activity and creativity, its cumulative capacity to create change. All animals have ways of living, some complex enough to be called cultures. Human culture alone is progressive; it has been increasingly built by conscious choice and selection within it as well as by accident and natural pressure, by the accumulation of a capital of experience and knowledge which man has exploited. Human history began when the inheritance of genetics and behaviour which had until then provided the only way of dominating the environment was fi rst broken through by conscious choice. Of course, human beings have never been able to make their history except within limits. Those limits are now very wide indeed, but they were once so narrow that it is impossible to identify the fi rst step which took human evolution away from the determination of nature. We have for a long time only a blurred story, obscure both because the evidence is fragmentary and because we cannot be sure exactly what we are looking for.

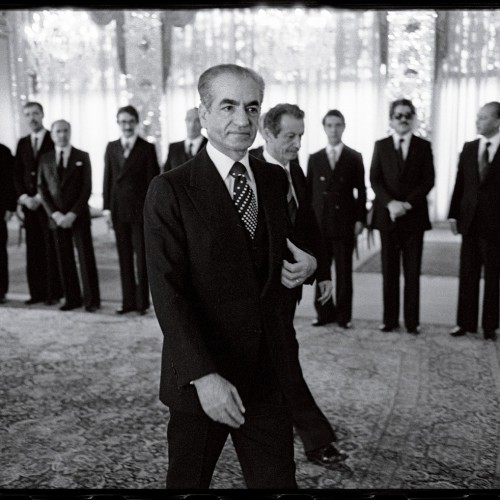

What Led to Such an Uprising in Iran?

What Led to Such an Uprising in Iran?