All three of the monotheistic faiths have developed similar theologies of election at different times in their history, sometimes with even more devastating results than those imagined in the book of Joshua. Western Christians have been particularly prone to the flattering belief that they are God's elect. During the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the crusaders justified their holy wars against Jews and Muslims by calling themselves the new Chosen People, who had taken up the vocation that the Jews had lost.

Calvinist theologies of election have been largely instrumental in encouraging Americans to believe that they are God's own nation. As in Josiah's Kingdom of Judah, such a belief is likely to flourish at a time of political insecurity when people are haunted by the fear of their own destruction. It is for this reason, perhaps, that it has gained a new lease of life in the various forms of fundamentalism that are rife among Jews, Christians and Muslims at the time of writing. A personal God like Yahweh can be manipulated to shore up the beleaguered self in this way, as an impersonal deity like Brahman can not.

We should note that not all the Israelites subscribed to Deuteronomism in the years that led up to the destruction of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar in 587 BCE and the deportation of the Jews to Babylon. In 604, the year of Nebuchadnezzar's accession, the prophet Jeremiah revived the iconoclastic perspective of Isaiah which turned the triumphalist doctrine of the Chosen People on its head: God was using Babylon as his instrument to punish Israel and it was now Israel's turn to be 'put under a ban'. They would go into exile for seventy years. When King Jehoiakim heard this oracle, he snatched the scroll from the hands of the scribe, cut it in pieces and threw it on the fire. Fearing for his life, Jeremiah was forced to go into hiding.

Jeremiah's career shows the immense pain and effort involved in the forging of this more challenging image of God. He hated being a prophet and was profoundly distressed to have to condemn the people he loved. He was not a natural firebrand but a tender-hearted man. When the call had come to him, he cried out in protest: 'Ah, Lord Yahweh; look, I do not know how to speak: I am a child!' and Yahweh had to 'put out his hand' and touched his lips, putting his words on his mouth. The message that he had to articulate was ambiguous and contradictory: 'to tear up and to knock down, to destroy and to overthrow, to build and to plant.' It demanded an agonising tension between irreconcilable extremes. Jeremiah experienced God as a pain that convulsed his limbs, broke his heart and made him stagger about like a drunk. The prophetic experience of the mysterium terrible et fascinans was at one and the same time rape and seduction:

Yahweh, you have seduced me and I am seduced, You have raped me and I am overcome ... I used to say, 'I will not think about him, I will not speak his name any more.' Then there seemed to be a fire burning in my heart, imprisoned in my bones. The effort to restrain it wearied me, I could not bear it.

God was pulling Jeremiah in two different directions: on the one hand, he felt a profound attraction towards Yahweh that had all the sweet surrender of a seduction but at other times he felt ravaged by a force that carried him along against his will. Ever since Amos, the prophet had been a man on his own. Unlike the other areas of the Oikumene at this time, the Middle East did not adopt a broadly united religious ideology. The God of the prophets was forcing Israelites to sever themselves from the mythical consciousness of the Middle East and go in quite a different direction from the mainstream. In the agony of Jeremiah, we can see what an immense wrench and dislocation this involved. Israel was a tiny enclave of Yahwism surrounded by a pagan world and Yahweh was also rejected by many of the Israelites themselves. Even the Deuteronomist, whose image of God was less threatening, saw a meeting with Yahweh as an abrasive confrontation: he makes Moses explain to the Israelites, who are appalled by the prospect of unmediated contact with Yahweh, that God will send them a prophet in each generation to bear the brunt of the divine impact.

There was as yet nothing to compare with Atman, the immanent divine principle, in the cult of Yahweh. Yahweh was experienced as an external, transcendent reality. He needed to be humanised in some way to make him appear less alien. The political situation was deteriorating: the Babylonians invaded Judah and carried the king and the first batch of Israelites off into exile; finally Jerusalem itself was besieged. As conditions got worse, Jeremiah continued the tradition of ascribing human emotions to Yahweh: he makes God lament his own homelessness, affliction and desolation; Yahweh feels as stunned, offended and abandoned as his people; like them he seems bemused, alienated and paralysed. The anger that Jeremiah feels welling up in his own heart is not his own but the wrath of Yahweh. When the prophets thought about 'man', they automatically also thought 'God', whose presence in the world seems inextricably bound up with his people. Indeed, God is dependent upon man when he wants to act in the world - an idea that would become very important in the Jewish conception of the divine. There are even hints that human beings can discern the activity of God in their own emotions and experiences, that Yahweh is part of the human condition.

As long as the enemy stood at the gate, Jeremiah raged at his people in God's name (though, before God, he pleaded on their behalf). Once Jerusalem had been conquered by the Babylonians in 587, the oracles from Yahweh became more comforting: he promised to save his people, now that they had learned their lesson, and bring them home. Jeremiah had been allowed by the Babylonian authorities to stay behind in Judah and to express his confidence in the future, he bought some real estate: Tor Yahweh Sabaoth says this: "People will buy fields and vineyards in this land again." ' {46} Not surprisingly, some people blamed Yahweh for the catastrophe. During a visit to Egypt, Jeremiah encountered a group of Jews who had fled to the Delta area and had no time at all for Yahweh. Their women claimed that everything had been fine as long as they had performed the traditional rites in honour of Ishtar, Queen of Heaven, but as soon as they stopped them, at the behest of the likes of Jeremiah, disaster, defeat and penury had followed. Yet the tragedy seemed to deepen Jeremiah's own insight. {47} After the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple, he began to realise that such external trappings of religion were simply symbols of an internal, subjective state. In the future, the covenant with Israel would be quite different: 'Deep within them I will plant my Law, writing it in their hearts ...'

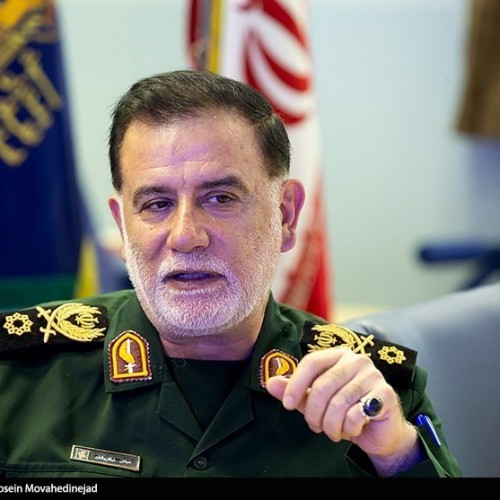

Israel Hatching Plots to Make Up for Defeats: Iranian General

Israel Hatching Plots to Make Up for Defeats: Iranian General