All three confederations succeeded in this, but only the third of them, the Safavids, had lasting success. The first of these Turkmen confederations, the Qara Quyunlu, began their endeavours in the 8th/14th century, establishing a principality the capital of which eventually became the Persian metropolis Tabriz. In 872/1467, when at the height of their power, they were defeated in armed conflict by the rival Aq Quyunlu, who after their victory also transferred their capital to Tabriz. In 907/1501 the city then became the capital of the third confederation of Turkmens, the Safavids, after they had in turn overcome the Aq Quyunlu. Like their two predecessors, the Safavids extended their domain to cover the whole of present-day Iran, an intervention in the fortunes of the country which proved of great significance for the whole development of Persia in the modern era.

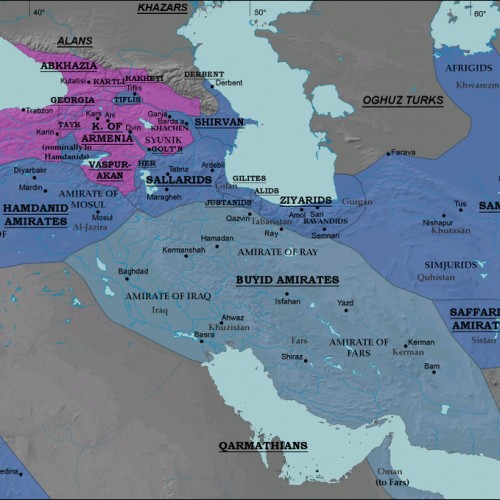

How is one to explain these movements of population and the centuries-long interest of Turkish tribes in Iran, a country whose people were neither Turks nor Turkish speakers? True, the ancestors of the tribesmen in question had already been in Iran - during the course of the Oghuz migrations, mass movements of Turks into the Near East and Asia Minor — and come into contact with Iranian culture, some of them for the second time, since they had been exposed to the cultural influence of Iran in Central Asia even before their migration to the west. The state and court chancelleries of the confederations, as well as their chroniclers, used the Persian language, which in itself points to a certain degree of Iranicisation. This influence was, however, confined to a minute ruling class whose admiration for, and love of, Iran and its culture naturally cannot in themselves have triggered off migrations of whole tribes nor determined the particular direction of their movement.

More important was the fact that, as a rule, the Tiirkmens in question had no access to the Ottoman army, any more than their leaders had to the Ottoman military aristocracy, which offered few real openings to them either before or after the battle of Ankara: The Qara Quyunlu leader Qara Yusuf was not even integrated into the Ottoman forces when he sought refuge with • the Ottomans in flight from their mutual enemy Timur. At this time Ottoman power did not extend as far as eastern Anatolia, let alone to Azarbaijan or the Iranian highlands. In the power vacuum left behind after the death of Timur and the fall of his empire these areas offered good opportunities for politically motivated tribal leaders interested in establishing independent domains. To the broad masses of the nomads the prospects of rich spoils of war from the civilised country of Iran and extensive grazing grounds for their herds were unfailing attractions. Together with the restlessness and spirit of enterprise typical of nomadic life, they probably constituted sufficient motive for the eastward thrusts of Turkmen tribes and their federations, at any rate for the first two waves, those of the Qara Quyunlu and the Aq Quyunlu.

A quite different motive, however, underlay the third wave, that occurring under the Safavids. They were attracted by a sufl order, the Ardabil Safaviyya and by a religious concept which, at the end of the 9th/15 th century or perhaps somewhat earlier, had developed from vague beginnings in popular piety into a politico-religious ideology. This ideology aroused in its adherents enthusiasm, fanaticism and ultimately unconditional commitment - precisely those attitudes of mind associated with militant believers in Islam. The order's centre in Ardabll had always attracted men of piety from near and far, including Turkmen tribesmen, long before the aspirations of its masters became unmistakeably political. But in the second half of the 9th/15 th century the hitherto customary pilgrimages gave way to something quite different and the donations arriving in Ardabll at that time, far from being mere oblations as before, had probably been given with other purposes in mind.

What had changed? With the travels of Shaikh Junaid in Anatolia and Syria an intensive phase of Safavid propaganda had begun, and his marriage with the Bay'indir princess, a sister of Uzun Hasan, had both increased his prestige and made him, to a certain extent, an acceptable ally of the Tiirkmens. The importance of these two facts for subsequent developments can scarcely be overestimatjed. On the one hand the order was intensifying contacts with the Outside world; on the other it was effacing the dividing line between the two key national groupings in the region. As the descendants of a line of Gllani landowners, the Ardabll shaikhs were representatives of Persian agricultural life, and not Tiirkmens or nomads. Distinctions between nations of the kind familiar to us from later European nationalism were foreign to Islam and are scarcely applicable in this case. Yet the Persians and Turks incontestably sensed that they were essentially different, and this feeling frequently finds explicit expression in historical sources. Intermarriage between the two, in so far as it occurred at all, was not common. Junaid's marriage did not, however, remain the only example of a Tajik-Turkmen union, and these initial indications of a symbiosis might perhaps help to explain just why Turkish nomads should have chosen as their leader the Persian-born master of a religious order.1 Be that as it may, the activities of Junaid to which we have referred were significant factors in the formation of the third great Turkmen federation.

A brief look at the early history of the Safavid order should help to clarify these developments. The motives behind the formation of the fraternity were certainly religious in nature, but it also played a considerable role in economic and political life, even in the time of Shaikh SafI, who gave the family its name. Landed property, revenues from religious foundations, donations and other sources of income brought him economic influence, and in politics he was able to establish wideranging contacts, even with one so eminent as the Mongol Tl-Khan. His descendants, amongst whom the position of master of the order was usually handed down from father to son, likewise went on to achieve distinction in public life. Without going into further detail, it can now be seen that Junaid's intervention in politics did not represent a radically new departure. What was new was the way he, and afterwards his son and successor Shaikh Haidar, set about militarising the order. The organisational measures and reforms they carried out must have been of lasting effect, for they remained in force until Isma'Il came to public prominence decades later, in Muharram 90 5 /August 1499, this despite the fact that their two initiators, and after them Sultan 'All, lost their lives on the battlefield — three masters of the order in the space of thirty-four years.

Recent research has thrown more light on these matters even if some questions still remain unanswered. We now have at least some notion of how the alliance between Ardabll and its outposts worked, especially those in Anatolia and Syria that provided the main body of the forces which supported the Safavid seizure of power. Local cells existed under a headman, called a khalifa. In individual cases, though not as a general rule, there was a supervisor, called a ptra, who was responsible for their coordination. At the head of the organisation was the khalifat al-khulafa, who was also deputy of the master of the order (murshid-i kamil). It has not yet been possible to ascertain exactly when this organisation was established, but it is known that there was a khalifat al-khulafa as early as 1499, i.e. before Isma'lPs accession to the throne. Once the decision to seize power had been taken, the organisation demonstrated its efficiency.

Assertions in some sources that the young Isma'Il personally made this decision cannot be accepted at face value. Although he became master of the order five years earlier in place of his brother Sultan 'All, he was still merely twelve years old at the time of the march out of Gllan. Even if one assumes that he was abnormally gifted, it is still inconceivable that a boy of that age could have carried out the complex political and military planning and preparation that must have preceded the uprising. Who, if not Isma'Il, could have taken the momentous decision and begun to put the operation into effect? Some time ago, Soviet historians referred, if only in vague terms, to the existence of Turkmen confidential agents as advisers of Isma'Il.1 More precise information has since come to light. They were in fact a group of leading Turkmen tribesmen, the ahl-i ikhtisds ("those endowed with a specific responsibility" or "those legally empowered to act"), a sort of "central committee" as they were recently described in modern terminology. These were the people who sustained Isma'Il after the death of his brother, who made it possible for him to escape to Gllan and kept him in hiding there, who took care of his education and ultimately persuaded him to march against the Aq Quyunlii. In the light of this obviously convincing interpretation, the elaborate myth of Isma'Il the child prodigy becomes superfluous. Even so, the events associated with his public appearances remain extraordinary enough and messianic elements, evident even at the outset of his career, are now no longer mere surmise but have actually been proved to exist.

The hundred and fifty years of the Safavid order that culminated in the accession to the throne of Shah Isma'Il not only have their place in the religious history of Islam but are from the outset of political significance. Although there had always been a certain influx of Tiirkmens into the order, it was not until the time of Shaikh Junaid that the strong links with Turkmen tribesmen were forged, that made for an increasingly tight-knit organisation. His years of propaganda in Anatolia, in Syria and, of course, also in Azarbaljan ultimately unleashed the third wave of Turkish emigrants returning to the Iranian uplands and created the conditions necessary for the formation of the third Turkmen federation, which may be called the "Safavid" or perhaps, more accurately, the Qizilbash federation. This migration persisted, as has recently emerged,4 right up to the death of Shah 'Abbas I, a time when the Qizilbash had decades previously forfeited their privileged role.

Closely linked to these occurrences is a religious phenomenon the origins and earliest development of which, despite new information, have still not been adequately investigated. This is the decisive transformation due to the influence of the Shl'a. The fact that presentday Persian adherence to the Shl'a derives from the early Safavids, especially Shah Isma'Il I, might lead one in retrospect to conclude that a change of faith took place according to the principle emus regio eius religio. But appearances are deceptive. In reality the transition was a lengthy and highly complex process, connected with the spread of certain Shl'I ideas via Folk Islam or Islamic popular piety — a process which cannot be discussed in detail here.

FOUNDATION OF THE EMPIRE BY 'iMAD AL-DAULA

FOUNDATION OF THE EMPIRE BY 'iMAD AL-DAULA